The Last Interpreter

Inuit resilience in times of AI

Image from The Olio yearbook (1910), Amherst College., courtesy of Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons.

Clarence Birdseye could no longer afford tuition. He withdrew from Amherst College after his second year, as his family’s finances were in peril. Clarence tried various jobs, and one of them was for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) as an “assistant naturalist.” USDA hired him to help the farmers in New Mexico and Arizona learn more about coyotes that attacked their livestock.

Clarence was well-suited for the job. A sixth child in the family with nine, he was driven, curious, and persistent. Clarence was obsessed with natural science, taught himself taxidermy by correspondence, and was ready to teach it by age 11. His tenacity over the years culminated in him becoming a highly resourceful young man. The USDA was pleased with his work. For his third assignment, they sent him to Labrador, Canada.

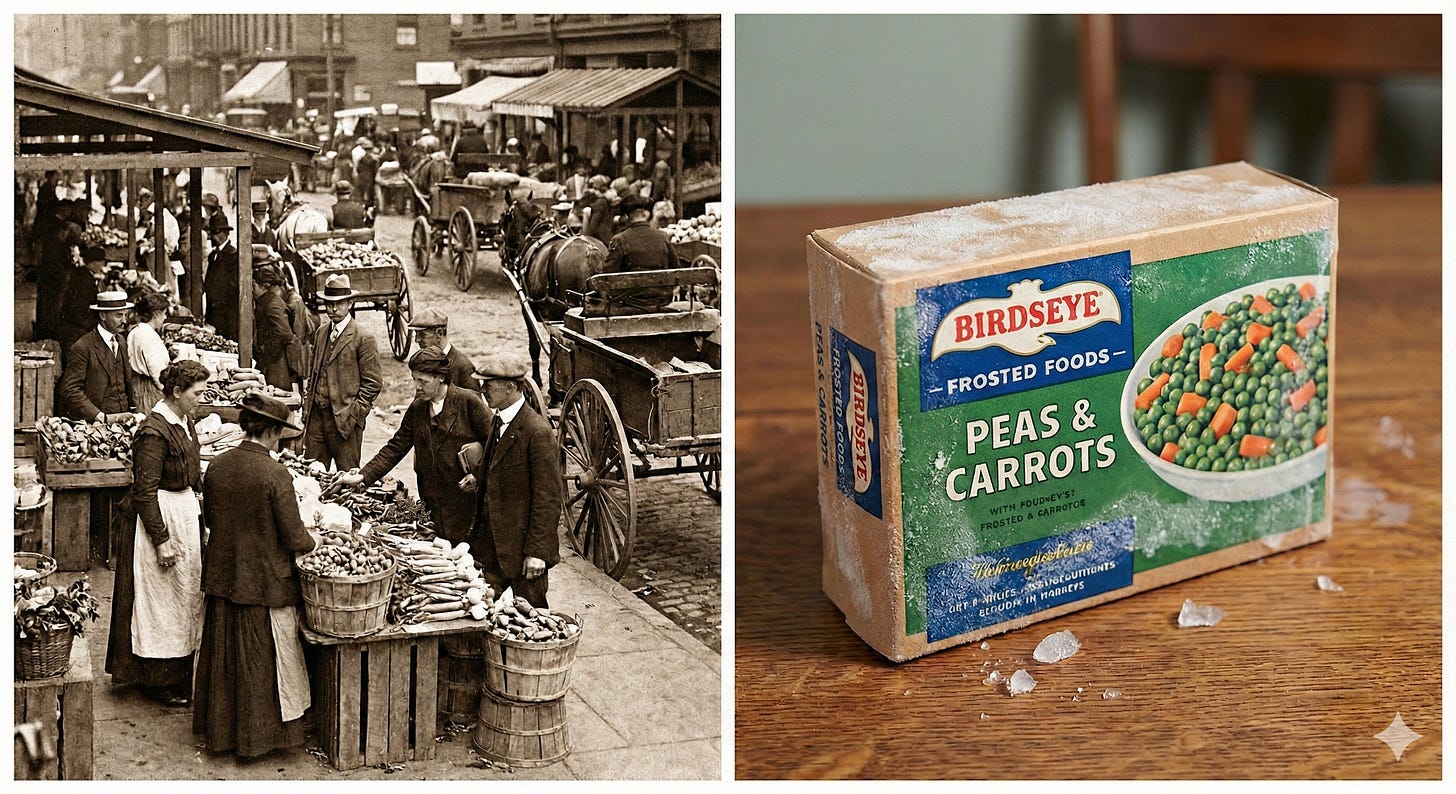

Clarence had never experienced -40 Celsius before. The local Inuit fishermen taught him ice fishing by drilling through thick ice. He noticed that the fish they caught were frozen quickly when exposed to very cold air. Thus preserved, the fish remained fresh and tasted nothing like the freeze-burned mush produced by the regular slow freezing method.

At that time, most food in the US was sold fresh. Much of it spoiled on the way to the market. Food was expensive - about 25% of the family’s budget. A significant part of the US labor force worked in the food industry, mostly in farming. In addition to the farmers, many US workers were employed in the “Natural Ice” industry. They harvested, stored, and distributed frozen water from lakes and rivers, and the ice was used to preserve produce.

Clarence patented the flash-freeze method and established a company that was later purchased by Goldman Sachs. This invention transformed the US food industry by significantly reducing food cost and spoilage. As you can imagine, there was no comparison of the flash freeze efficiency to the Natural Ice method. About 20% of the US workforce lost their jobs. Long-term, however, the unemployed food workers became employed elsewhere.

Image generated by Nano Banana Pro

Thomas Lee, the co-founder of Fundstrat, a boutique financial research firm, shared this story about Birdseye on a recent Prof. G podcast while discussing the currently prevalent story of AI taking our jobs. Delivered matter-of-factly, his history lesson had a soothing effect on the podcast hosts and the audience.

Another guest of the show, the University of Michigan professor Justin Wolfers, offered another insightful point. He said, “I am quite confident the last interpreter has been hired.” This dose of reality hit me. I could not have imagined hearing this 10 years ago.

Here are a couple more historical references from Dr. Wolfers.

Bank Tellers. When the Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) showed up, a widespread prediction was that the human bank tellers would become obsolete. What happened? We have just as many bank tellers now as we did before the ATMs. They have been reassigned to upsell the clients by offering them higher-margin financial services. Human contact beats a machine in sales, you see.

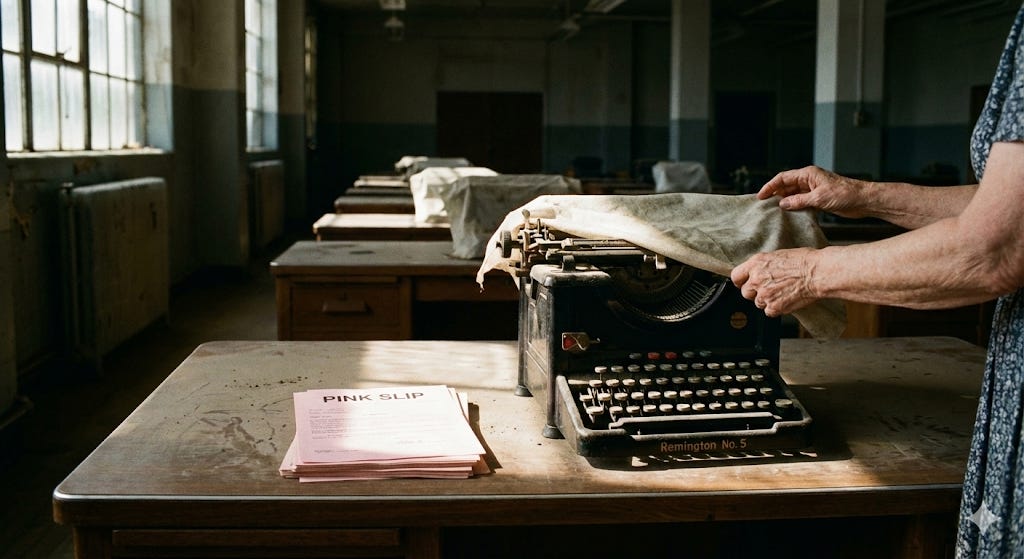

Typists was another historical reference Dr. Wolfers offered. Corporations had entire floors of typists in the 1950s and 1960s. This job was replaced by a word processor on a personal computer.

Image generated by Nano Banana Pro

Professor Wolfers followed his historical examples with some analysis.

The first point he made was that ownership mattered. To follow his mental experiment, imagine you are given a robot that can do your job. You are then liberated to pursue higher goals. Would you say “No” to that? Alternatively, imagine that the same offer was given to your employer, a robot that can do your job at 20 cents on a dollar. Same technology, different ownership, and you would not enjoy that at all.

Who owns the technology and has access to it becomes a crucial distinction.

The second point from Dr. Wolfers was a question of who stands to profit. Imagine a world where AI services are highly competitive. Anyone can get comparable results from Gemini, Claude, ChatGPT, Mistral, and from far less expensive AI options designed in China. The benefits in this scenario are distributed to all the consumers and employers, which means everyone. This is clearly not a “toll booth” business design where all the services go through one bottleneck; it is the opposite.

An alternative scenario is the “winner takes it all.” Then, the price can be controlled, everyone would pay up, and a single company at the center would rake in super profits. Such a scenario can be hardware-based, where all the AI competitors buy their chips in one place. We see this in the meteoric rise of Nvidia. It can be software-based, which is the narrative behind the “AI race” between Google, OpenAI, Meta, etc., or it can be licensure-based (e.g., the ARM Holdings, plc. business model). A certain entity, such as a country or a government controlling the key technology, can also try to become a monopolist.

An unregulated profit-maximization scenario will naturally gravitate toward the winner-takes-all solution. Anyone who has tried stock picking knows that a toll-booth-type design in business is ideal to maximize the Return On Investment (ROI). Investors nearly always prefer a monopoly and occasionally settle for a duopoly, such as Visa and Mastercard, controlling most digital payments worldwide. A monopoly is mathematically optimal when you optimize just one variable – the ROI. To be clear, this approach will not maximize accessibility, affordability, social well-being, equality, but only the ROI.

As game theory suggests, when one player wins massively in wealth distribution, all other players lose. That would be everyone who is not the owner or a shareholder of the said monopoly, statistically, most people in the world. A winner-takes-all is clearly not a win-win; it is a win-lose scenario, and this explains the mad race to the finish line.

A third point from Dr. Wolfers – jump on the bandwagon or bite the dust. Have you heard from individuals who despise the very mention of AI, for whom everything about this technology is just evil? We can certainly take a moral stance on nearly anything and endow a tool with human features, but is a hammer evil? One can use a hammer to kill a person or to build a house. It’s the user of the hammer who has intentions. To follow this metaphor, for now, while AI does not have human-like agency, we can consider it to be just a tool, comparable to a personal computer in the 1990s. An avoidance of learning anything about computers would have been a nearsighted approach for any corporation in the 1990s-2000s.

The bottom line here is that while AI is free or cheap to try, learning what it can do is likely a good idea for just about anyone. This tool can amplify your natural abilities in some areas. On the personal level, the return on investment can be massive – it is well worth investing your time and effort in learning this tool. That is a win-win.

What can I add to Dr. Wolfers and Mr. Lee’s insights?

A thought, “an AI may take my job,” suggests that a person thinking it is in the state of uncertain threat, which is anxiety. Nothing new here so far, people talk widely about the “Wall of Worry” in the markets now, but they refer to another looming threat – an expectation of the AI bubble popping.

Psychologically, then, we perceive AI as something brand-new, which makes it akin to an alien monster, dangerous and utterly unpredictable. We think that we have never experienced anything like that before. This “brand new” perception is like pouring gas on our anxiety system – we are far more anxious with novel threats.

Can the history lessons help here to some degree? Yes. You recognize some parts of the new story in the past events. Your mind goes: “Aahh, yes, we actually did see something like this before.” In fact, we have seen it many times, considering the printing press, electricity, personal computers, the Internet, etc. Collectively, as humanity, we survived all these game-changing events. Then, the first effect of the history lesson is that a powerful alien monster turns into a jack-o’-lantern. Spooky, but not deadly.

The second effect of history is that it allows us to zoom out. Things are especially scary when we focus on the near future, as in “I will lose my job in 2026.” History puts things in perspective and suggests that long-term, collectively, we tend to do okay with such changes.

The third effect of history is what happens to the most devout orthodox individuals who had considered the new technology to be anathema. Rabbis use Zoom now, and the Pope has a Twitter account. They no longer consider such technology to be the devil’s apple.

If we add the Stoics to the history lessons from Dr. Wolfers and Mr. Lee’s, to cite Marcus Aurelius interpreted by Pierre Hadot: “Do what you must, and what happens-happens.”

What can you do with these looming threats? You can learn. You can adapt, which is an essential part of evolution and survival. The world is changing rapidly, and, according to Yuval Harari, the rate of change is accelerating. The ultra-conservative individuals who are rigidly holding on to the past are less likely to survive in the fast-changing world.

If you consider AI to be just a tool, then learning how to use it in some suitable circumstances can be entirely within your control. This learning need not be a compromise. One can learn new tools without sacrificing one’s identity or values.

What else? Notice the passive structure in “My job will be taken by AI” statement. The active “I” is missing. Such a passive approach will predispose us to helplessness and anxiety, because things are entirely outside of our control; they are perceived as “forces of nature.” Then, we might feel as a fragile human surrounded by monstrous waves that are about to crush us.

“I am” is an antidote to the passive stance. Even this observation: “I am anxious” is more resourceful than a passive attitude, “this is happening to me”, because it allows us to be clear about the most immediate problem - our anxiety, accompanied by avoidance of learning about the threat. This combination anxiety + avoidance creates a self-sustaining cycle.

Is anxiety ‘justified’ when we think about AI? Yes. We don’t know the future. The question is – what level of anxiety is adaptive here? How deadly is the threat, and how imminent is it?

In and of itself, anxiety is not pathological; it is a necessary survival mechanism. Anxiety response is healthy when it is reality-based and calibrated. We run into problems when we react with too little or too much anxiety, which happens when we underestimate or overestimate the threats by a wide margin. With that in mind, the avoidance usually makes things worse - when we avoid the environment, our estimation of danger tends to become more detached from reality and anxiety goes up.

To summarize, getting an adequate education about the new technology may be useful if one wishes to not be in panic mode about it.

Have people and companies already misused AI? Yes, they have. Letting widely available Large Language Models (LLMs) be used by the public for medical or mental health purposes without a proper warning is dangerous. Such use has already led to harm, and the clinical applications of AI must be regulated. LLMs and LRMs (Large Reasoning Models) are not licensed clinicians, they do not bear any responsibility for their errors, and their clinical competence has not been independently verified. Using them for clinical needs is gambling, not healthcare.

Thus, we should maintain critical thinking and clarity on the boundaries of AI’s competence. This is just common sense, like using a hammer to build a house and not to inflict harm on others.

What else can help? A rapidly changing environment resembles turbulence. To survive in turbulence, one needs to maximize resilience and anti-fragility, which means physical and mental health, a robust social support network, and financial stability. Knowledge and experience make us more resilient, as does flexibility – we are more likely to adapt to changes when we have these resources and know how to use them.

The threat to our jobs? We are more likely to weather the storm when we stay active, flexible, and have a mindset of lifelong learning.